Justice Involved Women - 2019

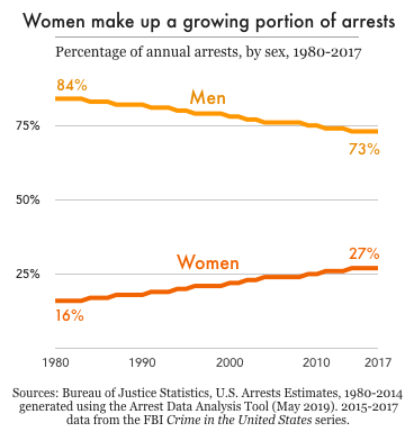

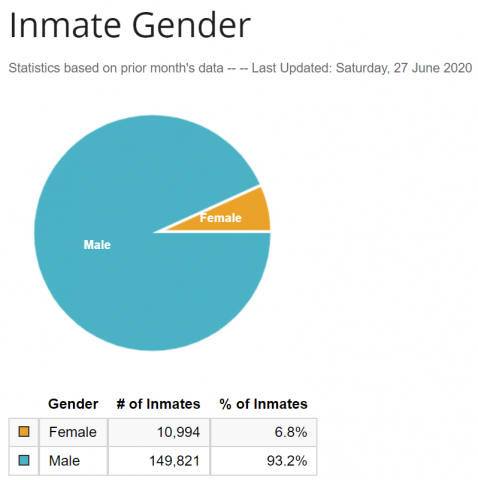

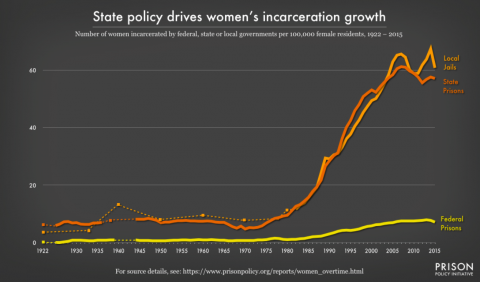

The number of justice-involved women has skyrocketed -- at rates exceeding men. Their entry into the criminal justice system, offense patterns, and levels of risk often follow a different path than men and require more targeted approaches.

The collection of resources below are intended to provide information on the back ground and current status of justice-involved women in the corrections environment in the United States. For more on this topic, please see our Justice-involved Women Project Page https://nicic.gov/justice-involved-women.